All creatures great and small on a database

Bob Cotter

Headteacher, Welton CE Primary School, Daventry Northants

This article first appeared in MicroScope Environmental Special Spring 1998

Welton CE Primary school lies in the rolling countryside to west of

Northampton and just north of Daventry, home of the once famous BBC masts. The village

school has 110 pupils and just four full-time teachers including the head. The school has

developed its work in IT over the past few years and this has been greatly helped by an

influx of portable computers in 1993. The work of the school often stretches out into the

local area and when it was asked to be involved in the establishment and development of a

'pocket park', a local community conservation scheme run by the Northamptonshire County

Council, the chance to be involved was quickly seized by the school. Welton CE Primary school lies in the rolling countryside to west of

Northampton and just north of Daventry, home of the once famous BBC masts. The village

school has 110 pupils and just four full-time teachers including the head. The school has

developed its work in IT over the past few years and this has been greatly helped by an

influx of portable computers in 1993. The work of the school often stretches out into the

local area and when it was asked to be involved in the establishment and development of a

'pocket park', a local community conservation scheme run by the Northamptonshire County

Council, the chance to be involved was quickly seized by the school.

One area where the school saw a value to both the 'park' and pupils was in monitoring

the wildlife that visited the park. The park is situated about 2 miles outside the

village, right near another of Northamptonshire's famous landmarks, the Watford Gap

Service Station on the Ml motorway. The park is situated on land that surrounds an

electricity substation and was donated to Welton Parish Council by East Midlands

Electricity. The site has an area of approximately one acre and initially contained areas

of established woodland and meadow. As it was an area in a potentially dangerous location,

the general public were neither inclined, nor encouraged, to visit the site, and as a

result it became a haven for wildlife which enjoyed the relative security of a

'people-free' zone. In fact it was area ripe for study for anyone, let alone a school. It

was an opportunity we did not wish to pass up.

Once the park was formally handed over to the parish in 1993 and officially opened in

the September of that year, the School moved in to monitor the wildlife. We were not

aware, until we started to collect information, that such a rich area for study was at our

disposal. The children's first examination of the park revealed just trees and grass and

on the surface it looked relatively uninteresting. Within a short space of time and

through regular visits during the early months of our work, we uncovered a wide variety of

evidence relating to the animals that regularly visited the park. During the Spring of

1994, we built a sizeable pond, with help from a local farmer and the local fire brigade.

The fire brigade found it particularly useful for trying out their new water tender and

kindly filled up the hole! This completed the three key types of habitat, adding water to

the existing woodland and meadow. The addition of the pond provided a superb area for pond

life studies and each creature found is dutifully recorded and logged on the database.

Other areas of the curriculum came in too... the making and siting of bird and bat boxes

has provided an element of technology… and the opportunity to be involved in tree and

hedge planting gave us lessons in science and conservation. There is still much to be done

and no doubt the work could continue well into the next millennium.

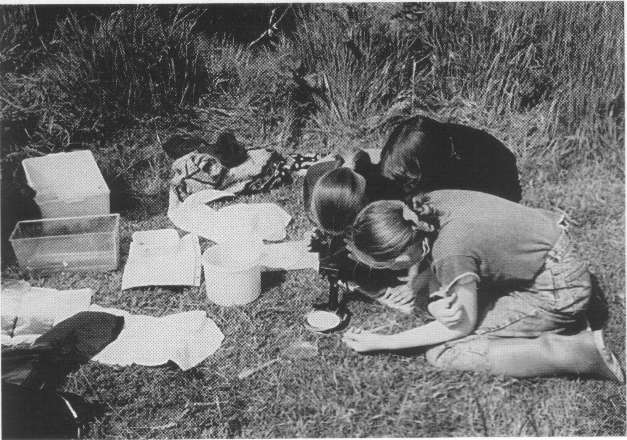

The children were warned that they were unlikely to see many animals in the flesh, so

they were encouraged to look for the 'evidence' to help them identify the creatures that

visited the park. A whole range of work grew around this project, putting into real use

the work they had done on 'the variety of life and living processes'. The need to store

the information was obvious and the use of a database seemed the most logical means of

doing this. Having a good supply of portables meant that the computers could be taken to

the site and the data recorded at the park. This took away the need for countless sheets

of paper and clipboards, the bane of most fieldwork. During the early months of the

project, a common sight was a 'snake' of year 5/6 children, weighed down by

identification charts and books and notebook computers, winding its way through the local

countryside en-route to the pocket park. During the course of that year many children

seemed to grow longer arms as the weight of the computers taxed their strength! Somehow

the return journey always seemed more arduous, whether it was the weight of the extra data

stored in the computer, we shall never know, but slowly the amount of information in the

database became more and more substantial. There were times when we longed to trade our

high grade Research Machines NB300 A4 notebooks into smaller palmtops or even 'pocket

book' computers.

The children used a database called Clipboard, produced by

Black Cat Software and stored on the hard disk in the RM 'Window Box' system. The database

is flexible and very good for storing the sort of information we needed, offering both

numerical and text data, along with a useful facility using 'keywords' to select the

appropriate wording for the data entry. The children used a database called Clipboard, produced by

Black Cat Software and stored on the hard disk in the RM 'Window Box' system. The database

is flexible and very good for storing the sort of information we needed, offering both

numerical and text data, along with a useful facility using 'keywords' to select the

appropriate wording for the data entry.

The children worked collaboratively to construct their own fields in the database and a

lot of preparatory work was carried out in classifying, sorting and analysing the type of

information we needed to set up the database. Once this was done we started to collect the

data. Three years later we are still collecting and have now added a variety of different

wildlife to the database. Early information collected saw evidence of foxes, badgers,

stoats, weasels, woodmice, grass snakes, rabbits, hares and, of course numerous birds.

Little owl pellets were found and examined and the contents gave us further evidence of

the likely creatures in the area. The skeletal remains of weasels and stoats were

fascinating to the children and their uncovering was reminiscent of an archaeological dig

rather than an environmental project. The children became experts at examining droppings

(and their contents!), looking for teeth marks on nut kernels and spotting tracks and

footprints. Each identified animal was recorded and the relevant details noted on the

database. Details of the evidence were also noted and as the types of evidence changed,

the database fields were extended. The occasional tramp enjoyed a visit too and we often

found evidence of his visits!

The winter proved a very good time for this type of work as tracks and signs were easy

to find. Even the fur of some hapless rabbit or the half eaten remains of a bird, gave us

vital clues as to the activity in the park when no-one was around. The rare sighting of a

live mammal was a highlight (with the exception of rabbits, which seemed oblivious to the

presence of children), but this was occasionally tempered by the sighting of a dead animal

on the adjacent road. The children were saddened when they found a dead fox one winter's

morning. The frosted remains, a fresh meal for carrion birds, lay in the gutter, having

been struck a fatal blow by a passing car. The fox had clearly visited our park on his

travels that night and would leave us no further evidence. However, I am pleased to say

other foxes have chosen to visit the park and one chose it as a final resting place; his

corpse is slowly rotting to provide the children with another 'gem' to find when we next

visit. One wonders if he had an inkling that he would add to the richness of the pocket

park.

By the time summer comes round the park is lush with growth and evidence of finding

larger mammals is scarce. The insects and birds take over and the project takes on a whole

new dimension. Dragonflies now dart across the pond and lay their eggs in the water.

Damselflies do likewise while their young terrorise the invertebrate life that quickly

colonised the pond. The meadows are thick with a myriad of insect life of all kinds.

Scorpion flies, frog-hoppers, shield bugs, worms and molluscs all form part of nature's

food chain and ever-new areas for study for the children. The speckled wood butterfly is a

common visitor and during the late summer they are in abundance. Frogs are now common and

the occasional newt has been uncovered, hiding under a stone. Evening visits are often out

of the question, but pipistrelle bats use the twilight to catch the insects for their

evening meal.

Now we only take two or three computers and the information is recorded by groups and

shared back at the school. The data is analysed, the habits and habitats of the creatures

are written up, and the information presented in written reports, graphs and charts. As

each season passes, the work is recorded and the visits are always eagerly anticipated by

the children. Some children take their parents at weekends and often will note any

creatures they find when they come back to school.

As the store of information steadily increases and the children change year groups, the

work remains interesting because children, as always, remain fascinated by wildlife. The

need to use this store of information is a future project and although the data will

continue to be collected, the opportunities are arising for putting together the findings

into the information leaflets for the general public. Thoughts of a CD-ROM package for the

rest of the school to share are also going through the mind. The latter idea offers a very

attractive development and could prove a very worthwhile task once the work can be

transferred onto an 'authoring' package.

The whole thing sounds very idyllic and it seems plain sailing. It has been hard work

and the evidence is occasionally thin on the ground. The national curriculum requirements

can impinge on the work and other work has to take a priority in the busy schedule of the

school. Software can sometimes let you down and portables have a habit of running out of

power just when you do not have an opportunity to recharge them, even if you do have a

high voltage electricity sub station within easy reach - connecting them up seems a little

risky! The portables are not always easy to see in the open, especially when the sun

shines brightly - and where do you keep the mouse? Then there was the time one summer when

we opened the computers up at school and various insects crawled from under the keys. It

put a new meaning into getting bugs in the computer. My service engineer can never work

out how we need grass cleaning out of the computer casings when he services them and I

dread to think what else he discovers! One thing can be sure, it leads to an interesting

time and work, even on a computer database, is never dull.

Finally, our pocket park database is an on-going resource and many children contribute

to it as terms roll by. You may think we are lucky to have such a resource and perhaps we

are. Most schools have access to areas where wildlife is in evidence, however, you cannot

always see it and you need to look carefully. You can even adapt an environment and

attract the creatures to you. Build a pond, put in plants that attract butterflies and

other insects, set up woodpiles and compost heaps and you'll be surprised what will come

to you. What we are creating, and you can do it too, is a store of information that is fun

to collect, has a relevant purpose and will be available to pupils in your school, as

future resource for years to come. Go on, try it!

[top of page]

|