Logical Zoombinis:

an adventure game for thinking

Steve Higgins and Nick Packard

Learning and Instruction Group

University of Newcastle upon Tyne

Logical

Journey of the Zoombinis is a captivating critical thinking program

designed around an escape story. The Zoombinis are a happy group

of creatures whose island is taken over by the Bloats. The player's

job is to help them in their escape. It is an unconventional mathematics

program, in that numbers and arithmetical operations do not play

much of an explicit role. Instead, this program focuses on the logic

and reasoning elements of mathematics: attributes, patterns, groupings,

sorting, comparisons, and problem solving. This may not be the current

focus for development in England and therefore hard to squeeze into

an overloaded school day. However the links with mathematical and

scientific reasoning, as well as with geography and history (are

the Zoombinis invaders or settlers?), or even the potential for

contributing to literacy, make the program justifiable for those

who see the value in it.

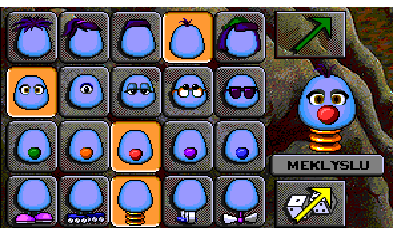

As mathematical creatures, the Zoombinis embody the powerful ideas

of attributes and combinations. Each Zoombini may have one of five

kinds of hairstyles, eyes or eyewear, nose colours, and feet or

footwear. Thus there is the possibility of forming 625 different

combinations. In their mathematical structures Zoombinis are similar

to records in a database, or base-5 numbers, and other mathematical

objects such as vectors. Zoombinis can therefore take part in many

mathematical processes related to data analysis, graphing, algebra,

and logic.

There are 625 possible combinations of attributes

Players must help the Zoombinis escape from Zoombini Isle and find

a new homeland. First you choose specific types of attributes for

each of the 16 escaping Zoombinis in your group. Once the team is

assembled they set out on a path that would make Indiana Jones tremble.

The Zoombinis confront a dozen obstacles that you must overcome

using deductive logic and creative reasoning. For example, the first

obstacle in their path is a pair of rope bridges at the Allergic

Cliffs. A guardian of these cliffs sneezes if a Zoombini with the

wrong attribute (or combination of attributes) tries to cross his

bridge. Make too many mistakes, and the bridge collapses. This requires

children to use sets and evidence to work out how to get all of

the Zoombinis across. Other activities include arranging the creatures

on a raft in a correct sequence, which develops comparison and pattern

skills; and hitching a ride on a toad placed on the correct shaped

or colour-coded lily pad to develop pattern identification and analysis.

A map is available for you to see where you have been and to try

puzzles in the practice mode.

At the hardest level you have to work out the likes and dislikes

of three pizza trolls with six pizza toppings and four ice cream

choices!

One of the more impressive features of this program is the potential

it has for repeated use, across a broad range of ages. Each of the

puzzles increases in complexity with each success. At the simplest

level five and six-year-olds can complete the puzzles. The hardest

levels of the hardest puzzles challenge adults! In practice mode

the program can be set at four levels of difficulty, which can be

useful for setting specific challenges to focus teaching particular

skills and accommodate different teaching and learning styles.

In the classroom

We

have used Zoombinis with different ages of pupils, from Year 3 to

Year 6. It has been successful on single machines as well as on

a network where a whole class used it (in pairs) on a weekly basis.

In general pupils collaborated well, though some needed encouragement

to share the mouse and to discuss and agree a course of action.

The program quickly becomes challenging to even the most able who

therefore found it useful to discuss what to do so that they did

not lose any Zoombinis. Successful pairings varied, with higher

attaining pupils sometimes being surprised at the ideas and suggestions

of friends usually less successful at more traditional tasks. The

level of motivation and task-related talk observed in all classes

was high.

Pupils' strategies

The more successful pupils used a combination of approaches. In

some of the puzzles you need to try something and risk making mistakes

in order to get feedback to work out what to do. In others, such

as Captain Cajun's ferryboat, you can plan a complete solution first.

It certainly seemed to help to get pupils to explain how to solve

the puzzles. Even some 'experts' found it difficult to articulate

why they were being successful.

Help strategies

A specific set

of help strategies was given to the children working with the program.

These were to:

Using help materials

The addictive appeal of the game is such that it is hard to get

pupils to use support materials while they are on the computer.

It was much more fun and engaging to play! Solving puzzles away

from the computer was one solution to this difficulty. For instance

by having a group of pupils use some of the activities in the teacher's

resource pack. This also helped to identify specific problems and

helped to make successful strategies clearer. In addition we designed

a series of help cards to support pupils' independent use of the

program. Although these were successful in helping them tackle the

problems, it was much harder to get them to record their attempts

to work out a solution. As a teacher, knowing when to intervene

directly is always difficult. Ideally probing questions can support

the pupils in structuring their ideas, but in practice this is hard

to do. In the end we decided that it was probably better to step

in after a brief interval and explain how to solve the puzzle then

see if the pupils had understood the approach the next time they

face a similar challenge. Of course knowing your pupils is also

essential, as some may request help too quickly. As the puzzles

are always different they need to understand principles rather than

solutions. Modelling a solution, or getting other pupils to demonstrate

a strategy, while explaining why it works seemed to be the most

helpful approach. Encouraging pupils to articulate their strategies

was easiest with the whole class arrangement, as it was possible

to begin and end sessions with a review or summary.

Challenges in teaching thinking

Each

puzzle offers four levels of challenge, and the difficulty level

automatically increases as player's master easier mathematics and

logic problems. Furthermore, all the puzzle solutions regenerate

with each attempt, so a player never faces the same puzzle twice.

The advantage of this is that you have to concentrate on principles

and strategies. It is possible to develop a shared language for

discussing strategies for problem solving with your class. Words

for talking about thinking help children to develop 'metacognitive

awareness', by which we mean not just thinking but thinking about

thinking.

The difficulty for the teacher is in knowing when to intervene.

Also, with a single computer used by two children at a time, it

is hard to justify interrupting your teaching to try work out a

solution and decide the best way to help. Most of the teachers using

it in this way expected pupils to manage on their own. Again the

help cards were useful in increasing independence, but some pupils

became frustrated at being unable to solve a puzzle without losing

lots of Zoombinis. Most children find it hard to grasp the idea

that mistakes can help you learn.

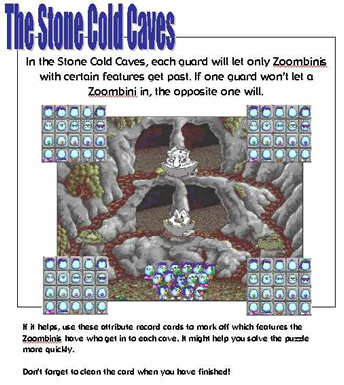

Which bridge should the last Zoombini cross and why?

Does it work?

The pupils we observed and worked with certainly became more skilful

at solving the problems in the software and more articulate in explaining

their strategies and solutions. The crucial question is does helping

the Zoombinis on their journey mean that these children will think

better in other situations? Is time spent with the Zoombinis going

to have an effect in their English lessons or on their capacity

to understand Mathematics? This kind of 'transfer' of learning from

one situation to another is always difficult to show. From our observations

the most important factor is the role played by the teacher. Teachers

can aid the 'transfer' of skills by making the thinking strategies

used with the Zoombinis more explicit and by drawing out connections

with different areas. For example the connection between problem

solving in the Zoombini world with questioning and hypothesising

in Science could be explained. Used in this way experience with

the Logical Journey of the Zoombinis can help to develop critical

thinking skills of the kind that are useful across the curriculum

and in many areas of life.

Steve Higgins and Nick Packard

University of Newcastle upon Tyne